Desmond Tutu: Spirituality, Social Justice and Leadership

07/04/2022

The Ecumenical Review: Volume 74, Issue 4

08/12/2022Economies of Violence 2023

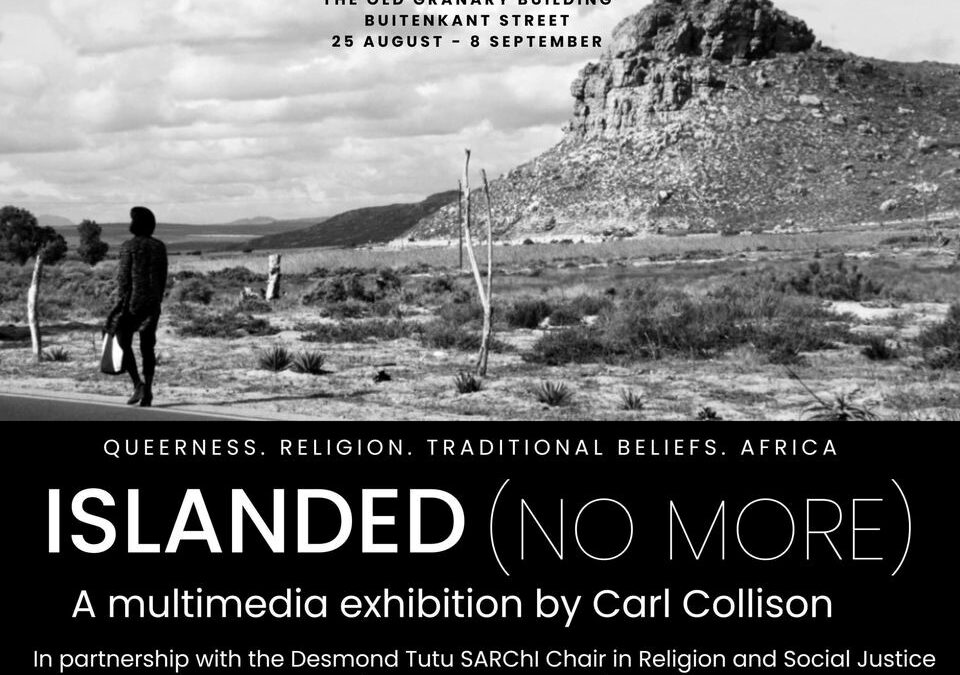

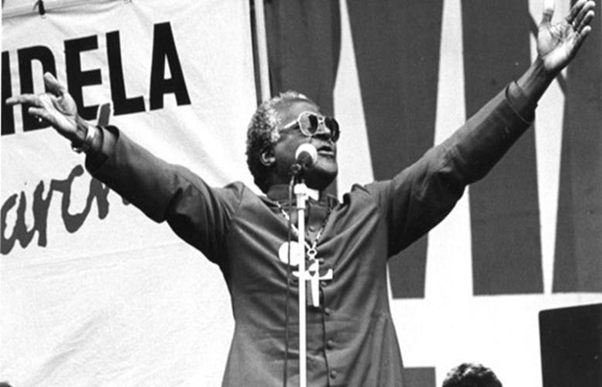

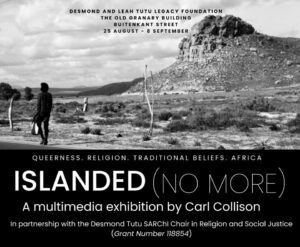

Since 2017, the Centre has been expanding trans-disciplinary research that intersects activism and academia, through the commemoration of the anti-apartheid women’s march of August 1956 and the Marikana massacre of August 2012. The annual event is structured through the theoretical lens of “economies of violence.” On 31 August, The Desmond Tutu SARChI Chair in Religion & Social Justice, in partnership with The Desmond and Leah Tutu Legacy Foundation hosted a Multimedia Art Exhibition as part of the annual commemoration. The exhibition was curated by Carl Collison, MA student in the Tutu Centre.

Collison described the exhibition as follows:

Islanded (No More) is a body of work I have been putting together over the past few years as a journalist and filmmaker covering the lived experiences of LGBTIQ+ people across Africa. The exhibition focuses on the intersections between queerness and religious and traditional belief systems in various parts of Africa. It is made up of photography, text and short documentary films and was on show at the Western Oregon University’s Hamersly Library gallery before coming to Cape Town.

After a guided exhibition, the event began with the lighting of a candle remembering queer lives lost to violence. Megan Robertson, who directed the program for the evening, provided a brief background to the event and the speakers, after which Sarojini Nadar posed various questions to the artist about his inspiration and probed into the motivations behind the exhibition in its current form. During the conversation, Carl invited two people who featured in the documentary films to join the discussion. Aurora Moses and Francis Mushambi each brought such special energy and thoughtfulness to their contributions on the panel. Their presence provided the real and embodied realities behind Carl’s art, as they each spoke passionately about how their struggles with religion intersected with race, ethnicity, sexuality and gender identity.

The audience participated through comments and questions around what it means to reclaim space in the realm of the sacred, when organized religion has been violent. As Extraordinary Professor, Miranda Pillay noted in her thanks, the seventh annual “Economies of violence” event achieved what we set out to do: To provide a platform to collectively examine how religion intersects with gender, sexuality, race and class to sustain the violence and violation that women, people of colour, people who are sexually and gender diverse, and marginalized men in South Africa disproportionately experience. Through the capturing of snapshots of the lived experiences of the queer people who featured in the exhibition, Carl Collison was also able to surface the potential of religion as a resource for those who experience queer-phobic violence. The evening ended with a powerful recital of Koleka Putuma’s poem “Every Three Hours” by MA student Tswelo Makoe.

Economies of Violence 2022

On 11 August 2022, the Centre hosted the 6th Annual Economies of Violence Public Lecture. This event takes place in August each year marked as it is, by two significant events in South Africa’s history: The anti-apartheid women’s march which happened on 9 August 1956 and the Marikana massacre on 16 August 2012, in which 34 miners were killed by the police at the Lonmin mine. These events bring up for scrutiny the “Economies of Violence” that continue to sustain the indignity and the poverty which women, queer people, and marginalised black people in South Africa disproportionately experience. This year the lecture was delivered by Extraordinary Professor in the Centre Khaled Beydoun and was the first time since 2019 that the event was held in-person. The lecture took place at the Desmond and Leah Tutu Legacy Foundation in the City Bowl and over fifty academics, students, religious leaders and other members joined for an evening of intellectual engagement, impassioned discussion, music and poetry.Reflecting on the North American context,Beydoun’s provocative lecture explored the tripartite dynamics of racism, gender and Islamophobia. In doing so Beydoun demonstrated the ways in which law as a critical tool for affirming and enforcing the sacrosanct character of human dignity, equality and esteem reinforces system of power and privilege, both discursive and material that at best alienate and at worst dehumanise Muslims across the gender spectrum.Following the lecture, celebrated poet and PhD candidate Pralini Naidoo accompanied by Afrikaaps performer Jitsvinger offered soulful contributions from Naidoo’s debut poetry collection Wild Has Roots.

Economies of Violence 2021

On 26 August 2021, the Centre hosted the 5th Annual Economies of Violence symposium, titled Religion, Resistance, and Rest. This was the second year in which the event was held virtually, due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This event takes place in August each year marked as it is, by two significant events in South Africa’s history: The anti-apartheid women’s march which happened on 9 August 1956 and the Marikana massacre on 16 August 2012, in which 34 miners were killed by the police at the Lonmin mine. These events bring up for scrutiny the “Economies of Violence” that continue to sustain the indignity and the poverty which women, queer people, and marginalised black people in South Africa disproportionately experience. The COVID-19 pandemic simply exacerbated this reality. The 2021 symposium considered the importance of resisting/transcending the epistemic violence which demands that black women focus on research and teaching that is perpetually located within pain and suffering. The keynote presented by Sa’diyya Shaikh titled, “Islamic Feminist Imaginaries: Love, Beauty, and Justice” reflected on examples of contemporary Muslim love ethics/politics as a way of moving toward gender inclusivity and social justice. Fatima Seedat responded by furthering the position that the personal is political, by discussing love and the spiritual as political. Farah Zeb, also considered spiritual reflections and practices which inspire joy and rest.

The complete roundtable discussion can be found in the African Journal of Gender and Religion, December 2021 issue https://journals.uj.ac.za/index.php/ajgr/article/view/1048/673.

The symposium was recorded and can be found on the University of the Western Cape’s YouTube channel https://youtu.be/vGJGUl06fZw.

Economies of Violence 2020

On 31 August 2020, the Centre held its fourth annual public lecture in commemoration of the 1956 Women’s March and 2012 Marikana Massacre. Under the theme of “Economies of Violence”, the annual lecture seeks to uncover the multi-faceted ways in which women, people of colour and marginalised men experience oppression and exploitation.

This year’s keynote speaker was Professor of Christian Ethics and African American Studies at Drew University (Madison, New Jersey), Rev Dr Traci West.

At the beginning of 2020, the DTCRSJ submitted a proposal to faculty to name this annual lecture (in its 4th cycle) after Jesse Hess. Jesse was an 18-year-old 1st year student, registered in the department of Religion and Theology at the University of the Western Cape who, in 2019, was found raped and murdered next to her 85-year-old grandfather who was also murdered in their home. While the faculty unequivocally voted in favour of the proposal, unfortunately the disruption of COVID-19 halted the process of application for this named lecture. However, during the proceedings of the 2020 EoV lecture her name was invoked as a reminder of the impetus for critical interrogation of the systems, beliefs and practices that reinforce and support violence against women.

The event was held via an online platform which allowed a total of 109 participants to join. This included a cohort of local and international guests. Vice-chancellor Professor Tyrone Pretorius and Dean of the Arts Faculty, Professor Monwabisi Ralarala opened the events with rousing reflections on the importance of intersectional inquiries into the multiple sites and systems of violence that characterise public and private life.

Lee Scharnick-Udemans and Megan Robertson welcomed participants on behalf of the Centre and framed the importance of the EOV lecture in 2020, highlighting how Jesse Hess’s life, murder, and constitutive absence holds great significance for the community of staff and students at UWC. They also noted that UWC was celebrating 60 years of existence and commemorated the strong tradition of the “university of the left” that consciously and intentionally opposes injustice – contained in its slogan – “hope through action.”

The event also made space for moments of reflection, as students of the Centre lit a candle in remembrance of victims and survivors of violent economic exclusion and gender-based violence. Poet, Veronique Jepthas, also performed her poem “Dear Mr President” which reflected the themes of the event (reproduced here with poet’s permission).

Dear Mr President

I come to serve you breakfast

And even spill a little tea on your fancy suit

Your silence echoes loud

And speaks 1000 words

I know you probably wanna forget

Move forward

Business as usual

But allow me to stop you in your tracks, preach and read you a verse.

This is verse 0-100

Of we have had enough of you and your ministers in your fancy suits, bullet proof cars and big houses paying us no regards

This is no time for you to be holding a press conference and offering your condolences

No time for you to be visiting families and offering them money while you get photographed to benefit your campaign

This is war so put your weapons to use

Blood has been flowing from one too many taps and in hope that it drips and drips and drips and drips on your fancy suit

So that the stain is impossible to get out.

I hope it stays as a constant reminder.

I hope it echoes loud.

I hope it screams something happened here.

I hope it screams something is happening in my country, I hope it screams I have been let down by my president.

May that echo in halls and churches and in schools and the grocery store

May it scream I was at home

I went to the post office

I was with my grandmother

I went to school

I was with my husband

I was only a babyI want you to know they have been born again in me and set my spirit alright

My house their names in my mouth and change my address to theirs

So that their names may dance gracefully from my tongue to broken records you have recorded for them

And I don’t know if you remember how the record goes but it goes like this

Nene

Courtney

Karabo

Reeva

Hannah

Amy

Veisha

Xolile

Noxolo

Zanele

Anyone

Mary

Barbara

Leighandré

Hope

Lynelle

Kamelle …If I didn’t know better I would think we are in hell

This is an attack on woman and an attack on your country

Could you please pay attention and load your presidential gun, please?

May the bloodstain on your fancy suit never wash out.

May it stay as a constant reminder.

May it scream something is happening in my country

May it scream I have been let down by my president.

In her riveting lecture, Traci West underscored the importance of disruption. Illustrating the ways in which racism and religion symbiotically co-operate in sustaining economies of violence, she called for disruptive methodological processes that in turn nurture an ethos of moral leadership. Among the elements due for disruption is the pervasive narrative of violence that tends to flatten the intersectional experiences of, for example, black women. This was a narrative that posits a binary between the victim who is shamed and the survivor who is celebrated – while neither is afforded empathy, resources or support, she argued. And further entrenching this binary and its harmful outcomes, which include the ubiquitous “strong black woman” trope, are generally the social, religious and cultural networks to which she might be affiliated. Intertwined economies of support, contended West, would therefore call us to look at the systems and structures from which this violence emanates, interrogate the beliefs that serve to excuse it, and from that vantage destabilise its presumed truths.

Disrupting economies of violence also means that concepts and practice must mutually inform each other as opposed to the top-down order traditionally preferred by the academy. West emphasised the need to question heteronormative understandings of women and men and how that might shape our ideas around autonomy. This allows for a humility in theorising and openness in practice that ultimately lend themselves to meaningful transformation. Seeming to value this in the delivery of this very lecture, the awareness of her own geo-political positionality saw her periodically pose questions to the South African-based audience, making sure to draw linkages between the two countries while leaving room for key differences to which she might not be privy.

Last, West called for a defiant spirituality, one that has the courage to confront hypocrisies and betrayals; Hypocrisies and betrayals that look like a constitution that affords women protection from violence in a country that reports the highest global rates of gender-based violence or a state that paints ‘Black Lives Matter’ on its most prominent road while upholding a mass prison industrial complex that destroys black communities or religious leaders who condemn abusers in word yet protect them in deed. She praised the efforts of Cape Town-based lesbian activist collective, Free Gender, applauding them for queering their definition of spirituality as well as their exceptional transnational Africana project. As she noted, transnational solidarity is crucial to destabilising economies of violence.

Watch the event here.

Report by Thozama Mabusela (Masters student)

Economies of Violence 2019

August is a significant month in South African memory, as we commemorate two events: the anti-apartheid women’s march which happened on 9th August 1956, and the recent Marikana massacre on 16th August 2012. These two events are a painful reminder of the ways in which “economies of violence” have, and continue to sustain the indignity and poverty that women, people of colour and marginalised men in South Africa disproportionately experience. As part of the commemoration, the South African Research Chair in Religion and Social Justice, and the Desmond Tutu Centre for Religion and Social Justice (DTCRSJ) convened a three-part symposium on the theme “Economies of Violence”, on the 1st August 2019. The symposium began with a roundtable discussion facilitated by Eusebius Mckaiser on Law, Gender, and Religion. The panellists were Pumla Gqola, Seehaam Samaai and Leigh-Ann Naidoo. This was followed by a commemoration of the 10 year anniversary of the book A Man Who is Not a Man by Thando Mgqolozana, and the day was concluded with a public lecture by Eusebius McKaiser on the theme ‘Marikana, Masculinities and Money’ with Zintombizethu Matebeni as the respondent.

This event spoke to the DTCRSJ’s commitment to the indivisibility of justice and to the centre’s mission statement i.e. “…to facilitate ongoing debate and dialogue on the intersections of Religion and Social Justice through conferences, workshops, seminars, symposiums and other collaborations with civil society…”. But it was also a day which allowed me to reflect on my own research and personal commitment to social justice. As a research assistant, Master’s student and as the Gender, Education and Transformation officer for Anglican students in Southern Africa, it challenged me to consider how my personal privilege, power and positionality impacts this commitment.

My Master’s project is focused on the responses of religious authorities to sexual violence. I was therefore intrigued by the panellist’s discussions on Law, Gender, and Religion as I was able to consider the ways in which religion and law are implicated in patriarchal violence and hierarchical gender binaries. However, it also brought moments of discomfort as panellists began to consider the idea of abolishing religion due to its deep involvement in the production, reproduction, and maintenance of sexual violence. I was unsettled because, while I am an activist for a gender-equal society without gender-based violence, I am also a Christian. And while I acknowledge that Christianity is implicated in systems of power such as heteronormativity, patriarchy, and androcentrism which produce economies of violence, my identity and meaning making system is also integrally tied to my religion – therefore abolishing religion would mean abolishing part of my narrative. Pumla Gqola mollified my discomfort by noting that religion and other social institutions need not be abolished, but because they have been developed within violent norms, it is those norms that have to be problematised and not the institutions themselves. Theoretically Pumla’s argument made sense to me however, I continue to wrestle with understanding how my religion can coexist with the notions of a non-gendered, non-hierarchical society while its key doctrines, Trinitarianism and Apostolicity, are embedded in hierarchy and power. I personally struggle with problematising my religions’ violent norms without the risk of being a heretic.

The 10th Anniversary celebration of ‘A Man Who is Not a Man’ also provided a moment for me to reflect on my relationship with literature. Pumla and Thando explored the common myth that black people do not read, let alone write. Thando pointed out that “black people do read however they do not have access to black literature”. This, for me, became a sad realization, especially because it reminded me of my own childhood schooling where we were constantly reading Shakespeare, Roald Dahl, and George Orwell due to the strategic ‘lack of black literature’. This influenced my thinking and imagination because I could only imagine stories as European or Western and if ever South African it would be the realities of white authors such as Sarah Penny. I therefore grew up believing that our stories are not worthy of being told in literature. However, Thando re-emphasised the fact that ordinary stories of people of colour are valid and worth telling too, hence he penned A Man Who is Not a Man. The idea of black people writing their own stories reminded me of Chinua Achebe’s words “Until lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter”.

The final part of the event was a public lecture delivered by Eusebius McKaiser with the theme ‘Marikana, Masculinities, and Money’. The lecture was introduced through two very symbolic and moving artistic renditions. The first was a performance by the University’s Choir of, “Senzenina?” a struggle song which laments, “What have we done?” This performance was an emotive one and as I saw a choir member shed a tear, I was reminded about the senselessness of the Marikana massacre and how the killing of those men represented the personal loss and violence many South Africans experienced daily. The second act which added to the pathos of the moment was the recitation by, Lee Scharnick-Udemans, senior researcher in the DTCRSJ, of “A Poem for Marikana” by Gillian Schutte. This was read whilst I lit the centre’s candle in honour and memory of the fallen comrades of Marikana. The public lecture discussed ways in which toxic masculinities intersects with hyper-capitalism to displace, destroy and disempower people of colour and marginalised men in South Africa by dehumanising male labourers and humanising inanimate things such as ‘the market’. In response to this Ntombizethu Matabeni, spoke of the exclusionary and sexist nature of remembering the names and faces of the men that were violently killed in Marikana. This narrow view of men and masculinities in Marikana ignores women in mining, female masculinities and a deeper exploration of the realities in Marikana.

The Economies of Violence symposium allowed me to reflect, and encouraged me to consider the ways in which the intersections between religion, law, gender, class, and race play a role in the production of violence in my own research. I was also challenged, as a black Christian man, to acknowledge the privilege that comes with my identity and how easily that identity can be used to justify the “economies of violence” which continue to sustain indignity and poverty. Perhaps we are too quick to ask for the end of exploitative capitalism without seeing the need to undo the contemporary forms of patriarchy in South African communities which so often coincides with our religious and cultural practices. To this end, I agree with Mfecane that, as researchers, we need to find ways “to end this capitalist ethic of greed so that black African men become caring, sociable, responsible and averse to the use of violence, exploitation, and the sexual abuse of others as a means to proving their power” (Mfecane, 2018), perhaps that is our only hope.